This begins a series of essays that apply the aesthetic framework developed in reviews of contemporary weird novels to recent films. The scenes, stories, and sensations that animate weird novels may be found as frequently in visual narratives; indeed, the 21st century has seen a new set of cinematic tropes—those of “found footage” films—that rediscover narratological structures deployed in Gothic novels and 19th/20th-century weird tales.

As with the literary weird, the cinematic weird is not easily segregated, stylistically, chronologically, or culturally, from the field of aesthetic production in general. Since Georges Méliès’ The Vanishing Lady, The Haunted Castle, and A Nightmare (all made in 1896), the weirdness of film has also been one of the medium’s abiding themes, with bizarre and uncanny scenarios, odd and queer characters, and dreadful monsters appearing, ghostlike, in the projector’s wavering beam.

Needless to say, cinematic weirdness takes many forms. My goal in these essays is to create a constellation of texts by which to guide future analysis. This initial post has three specific objectives: to establish a guiding distinction between horror and weirdness in film; to sketch out the aesthetics of contemporary cinematic weirdness by tracing several visual traditions that inform recent films; and to offer a close reading of an exemplary film, Liam Gavin’s A Dark Song (2016).

Weirdness v. Horror

There is no pre-existing category within the field of cinematic production and consumption that corresponds to “weird cinema.” The films under review are categorized as “horror,” “surreal,” “experimental,” “thriller,” and so forth. More importantly, the popular conception of “weird” is grossly inadequate to an analysis of the aesthetic sensations that should be classed as such. In earlier posts, I argued that the current “Lovecraftian” conception of weird fiction fails for several reasons: it subsumes weirdness under the category of horror; it prioritizes a singular mood or tone (that of “cosmic dread”); it (only/always) objectifies the encounter with the Real; it reifies racist, heteronormative and nationalistic figures, scenes, and stories; and through a combination of the above, it obscures a more nuanced, multicultural, and antinormative tradition. Many of the best weird novels belong to this larger, more enduring tradition.

The same may be said for contemporary film. Today, the category of “horror” subsumes many films that might better be termed weird, while other very weird films remain uncategorizable. This is particularly true of films in the “found footage” style, which are generally labelled as “horror” by critics who bemoan the genre’s lack of horror. Like all other affects, terror, fear, and abjection are inevitable and important elements in our culture. I am not, in what follows, arguing against the cultural sensation of horror. But I am railing against its use as an umbrella term that obscures more than it reveals. Let horror be horror and let the many fans of horror rejoice; but the stew of shared sensations thickens when we recognize the multiplicity of feelings evoked by popular culture, and that is my goal.

In truth, weirdness and horror, regarded as aesthetic sensations induced by the language of cinema, are worlds apart. Although they are often interlaced in film narratives, these sensations are neither co-constitutive nor interdependent. Pause to consider the differences between the affective relations that constitute the open-ended sensation of weirdness and the severance of those relations, which constitutes the horror scenario. The sense impressions and intellectual conceits associated with weirdness—from the odd and strange to the uncanny and incomprehensible—share a quality—let us call it expectation—which horror cancels. Curiosity, uncertainty, anticipation, and dread connote the unfolding dislocations and relocations that weird events make apprehensible. These senses of the world are “lively”; they are premised upon on-goingness, an anticipatory future in which meaning continues to dislocate or is restored. By sharp and often painful contrast, horror—be it conveyed via shock, violence, or abjection—ends expectation. The fear of horror is the anticipation of the end of anticipation, the fear of death. This is quite different from the uncanny terror of the unknown. Weird affects initiate an opening to what is not, while horror brings what is to an end. The first is the looming expectation of the winding road, the second is stomping on the brakes—too late.

The distinction is easily discernible in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), which, yes, I am about to “spoil.”

What are the weirdest features of the film? The Gothic house; the odd mannerisms of Norman Bates; the unexpected narrative twist; and the Freudian psychology that motivates the murders. What are its most horrific moments? The shower scene, Arbogast’s murder, and the final revelations—Norman in drag and his mother’s corpse. Each of these horror scenes severs or puts an end to the curiosity/ uncertainty/ dread that is evoked by the film’s odd and uncanny scenarios. To the extent that our knowledge of previous violence contributes to our sense of uneasy anticipation (e.g., when Arbogast and then Lila and Sam enter the motel), this dread (Ann Radcliffe calls it “terror”) is different from the uncertainty and uneasiness we experienced earlier in the film, when following Marion’s narrative. The tension of horror (a killer is lurking) has a singular focal point (usually the protagonist’s body in space) which might be distinguished from the more “open” or “uncertain” focal point of weirdness, which invites us to wonder whether or not there might be something going on. This is where weirdness closely resembles the suspense associated with thrillers.

Weirdness opens a door to the unknown, perhaps the unknowable. We are lost in weirdness. Horror, on the other hand, forecloses the possible. Horror finds us; we find ourselves in it, at the end. That foreclosure is symbolized in film by images of death or abjection. As in Psycho, these scenes are often conveyed cinematically through structural and symbolic shocks to the viewer’s psyche—rapid cuts and shifts in perspective, combined with terrifying images, reorganize our sense of sensation—we jump in our seats, spill our popcorn, gasp, shriek, laugh. Such affective responses are different from the silent, focused, uncertain and anticipatory scanning of narrative and visual scenarios that accompanies weirdness. Encountering the strange evokes a hypersensitivity to the non/normative; it generates a potential for the unusual (first step on the road to the impossible) to emerge within/alongside/in opposition to the ordinary. Consequently, weirdness courts the unexpected, the unusual, the surprising and original; horror, by contrast, is always the same. It may be sudden or prolonged; it may be unexpected or anticipated; it may be realistic or cartoonish; in every case, the moments of horror are repetitions of a singular affective event: the closure of the possible. Regarded in this light, weird affects may anticipate horror scenarios (the false perception that they inevitably do contributes to the centrality of dread for the Lovecraftians), but the sensations are neither organically linked nor similar in quality.

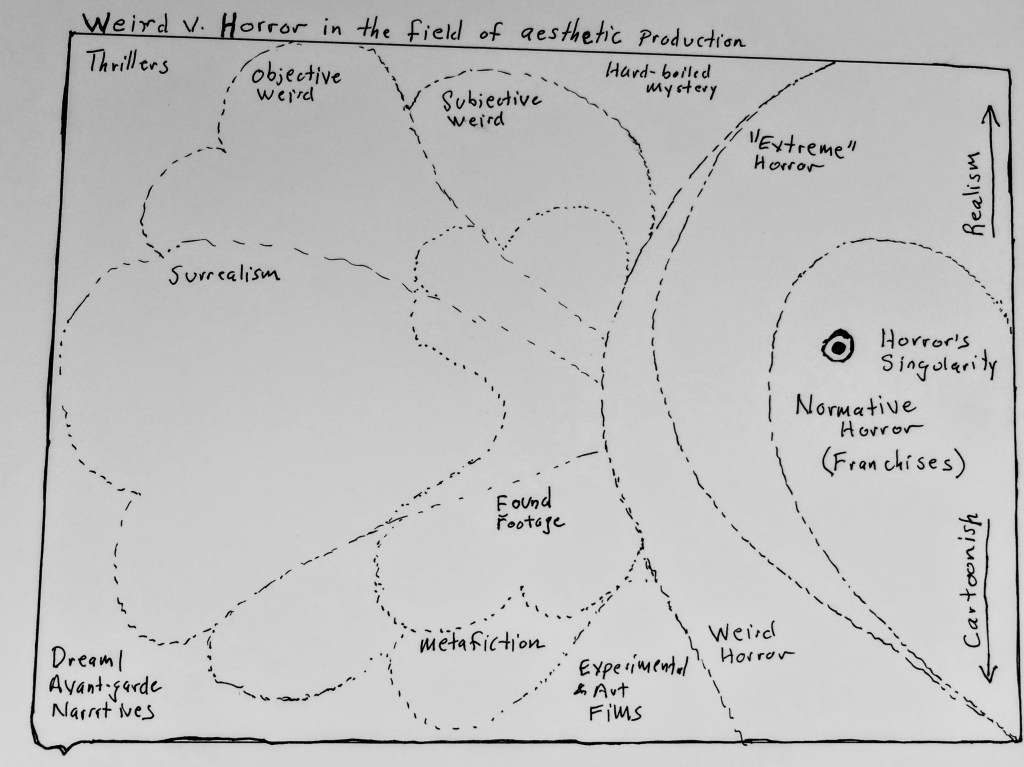

Once the affective difference between weirdness and horror is conceptualized, the generic differences between horror films and weird cinema are easily untangled. At either end of the spectrum, we may imagine two gravitational poles: one pulls outward, toward weird, unsettling, uncanny affects and the other inward, toward what I will term the “normativity of horror.” The latter is obvious in countless franchises (Dracula, Godzilla, Psycho, Halloween, Friday the 13th, Scream, Saw, etc.), which are, by the time they reach their second or third reincarnations, “pure” horror films to the extent that they present minor variations on horror’s singular scenario. It is no accident that such films tend to reproduce normative categories of identification and highly formulaic plotting; they symbolically defang the horrible by repeating its most generic scenes ad nauseum. The Jurassic Park / Godzilla movies created in the last couple of decades are obvious examples; death is gratuitous (half the time, we’re siding with the monsters) and the violence is used to police normative gender and class roles. Horror is reduced to a general thrill of being in proximity to mayhem for our protagonists (inevitably scientists or other members of the military industrial complex, plus some cute kids), who seldom encounter anything strange; on the contrary, they always already know what’s going on. Certainty is the cornerstone of these films, which align the monster’s creative destruction with national military powers. What could be more square? At this edge of my imaginary diagram, horror bleeds into that nebulous genre of “action/adventure,” which, however unrealistic, tends toward the normative mainstream.

Further from this pole, we may imagine less idiotic, more realistic, intensely horrific films, such as those often labelled “torture porn” or “New French Extremity.” Trouble Everyday (2001), Irreversible (2002), and High Tension (2003) are among the earliest and best of this subgenre, in which I would include such realistic, nihilistic, and gory films as films as Antichrist (2009) and The House That Jack Built (2018). Spectacular violence and sustained scenes of abjection propel these visual narratives, many of which have also raised controversy due to their homophobic, sexist, and nationalistic perspectives (or those of their makers). Although much more visceral, the intensification and prolongation of the horror scenario (as well as it’s totalization in apocalyptic films) serves the same ends as the goofy repetitions of the franchises: it confronts us with horror’s nihilism. Horror has nothing to say—which is not to say that it is not a valuable experience, but that it reproduces narratives to assassinate them. No wonder so many horror stories recycle so few plots. Within the field of the franchises, this quality is celebrated through a kind of ritual, goofy defanging realized through repetition of the grotesque and terrifying. These “extreme” films perform a similar action, but with realism and social satire dominant; nonetheless, many of them share a nihilistic relation to horror’s singularity: it is a foregone conclusion, around which the shit (it’s all fantasy, anyway) circles. By contrast, the horror films of Michael Haneke (Benny’s Video (1992), 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994), Funny Games (1997)) recognize the unspeakable of horror. They are distinct from those of Lars von Trier, Eli Roth or Tom Six because they take death seriously.

Near the middle of my imaginary diagram are horror narratives that introduce weird elements, while remaining predominantly organized around the horror scenario. Here we may find campy postmodern “classics,” such as Re-Animator (1985), Evil Dead II (1987) and some of the Freddie Kruger movies. Recent examples include The Cabin in the Woods (2011), Witching and Bitching (Las brujas de Zugarramurdi) (2013), Castle Freak (2020) and Freaky (2020). In such films, we find supernatural creatures (zombies, witches, Old Ones, body swaps), as well as significant amounts of grotesquery and body horror, accompanied by an anti-realist, cartoonish texture. These movies sublimate the uncanny by intellectualizing it (although not as fully as “torture porn” films do). That may sound strange, given how anti-intellectual these films are; yet they present the impossible as a conceit rather than a source of narrative intensity. This is why they revolve around generic “slasher” scenarios, despite the magical elements, and rely upon allusions to other films. In these narratives, acceptance of the impossible is merely a given—after all, as the Scream franchise reminds us, it’s just a movie.

On the border of these narratives, we find “body horror,” which merges the abject realism of “extreme” horror with the age-old body dysmorphia of “classic” horror. David Cronenberg is obviously the maestro here, although homage to Yuzna’s Society (1989) should always be paid.

The other pole, that of the weird, magnetizes the disconcerting, unaccountable, extraordinary, queer, and curious. Such films may or may not present us with supernatural entities or monsters of any kind. (Consider, for example, the absence of any monster in the most popular weird film of the past 25 years, The Blair Witch Project.) These films share a commitment to discovery and may evoke dread—although this sense of fearful anticipation is not in itself necessary. They include films labelled “surreal,” “experimental,” “satire,” or “arthouse,” but also many that fall, however uneasily, under the category of horror. In the next section, I diagram an overview of the various modes by which weirdness is evoked today.

Subjective and Objective Realism, Surrealism, and Metafiction

Cinematic weirdness may be identified by the aesthetic modalities through which the sense of dislocation and the potentiality of the impossible is achieved. For brevity’s sake, I cite a handful of predominantly postwar films to illustrate these tropes.

Weird narrative requires realism; the world must be presented as natural, normative, ordinary for the strange, queer, otherworldly to emerge. Films may be strange from the start, or unplotted, but weird narratives, in film as in fiction, develop a “real” world which is rendered strange to produce uncanny effects. In literary texts, as Todorov observes, fantastic plots are sustained by prolonging the “hesitation” or uncertainty that exists, for characters and readers, regarding the impossible. Weird texts are those which make the extenuation of this affect the driving force of the story, which may or may not end in horror.

In written texts, a variety of narrative styles prolong this uncertainty. A first-person, limited narrative reveals or conceals the impossible thing differently than a third-person, omniscient narrative. Free indirect discourse, which blends objective, omniscient narration with subjective, internal narration, is often employed to great effect by weird authors, such as E.T.A. Hoffmann, Henry James, and Shirley Jackson, and writers may also combine several styles in one story, as Hoffmann does in “The Sandman.” Visual narratives have less flexibility in the construction of subjective narrative, although “found footage” techniques have been used to develop a visual language of “embedded,” “first-person” perspectives and meta-narratives. Despite the inherently “objective” framework of the traditional cinematic image (in which the camera is an unrepresentable, objective window onto reality), montage and framing has long been used to present viewers with a particular character’s perspective on reality (i.e., the film’s diagetic “real world”). It is seldom difficult for viewers to identify (and identify with) the protagonist of a visual narrative, and to recognize the camera’s perspective as simultaneously objective and motivated by the protagonist’s perspective. This ‘normal’ language of cinematic signification is denatured in various ways to generate weird effects.

Examining the interplay between subjective and objective cinematic realities allows us to apprehend the primary modes by which weirdness is conveyed. I term “subjective,” those visual representations that, in the narration, prove to be uncanny forms of misidentification: the subjects of the narrative are confronted by disconcerting, apparently impossible images that turn out to be the result of ‘natural’ or ‘real-world’ forces. As viewers, whatever we saw or think we saw, was either an optical illusion or a subjective distortion of reality. As in Radcliffe’s novels or most stories by Poe, the supernatural remains a paranoid, hysterical or neurotic projection of the protagonist’s fantasies. Such films remain firmly in the “real world,” while interrogating the relationship between the apparent objectivity of audio/visual recording technology and the subjective interpretation of this reality. Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1938), Kukor’s Gaslight (1944) or Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate (1962) exemplify narrative and visual techniques that create radical uncertainty on the part of protagonists and viewer, without introducing supernatural elements. More recent films in this mode include Altman’s Images (1972), Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), de Palma’s Blow Out (1981) and Body Double (1984), Penn’s The Pledge (2001) and Soderbergh’s Unsane (2018). These films are most frequently categorized as dramas or thrillers, but we may see in them an important aspect of weirdness: the protagonist’s disorientation within diagetic time/space. Objective reality remains intact, but perceptions of that reality are presented to us through sequences that evoke the protagonist’s experience of disorientation and delusion. Our protagonist is accused of hysteria, paranoia, etc., but the plot will validate their perception, and therefore, ultimately, our trust in the “truth” of the visual realism the brings us the story.

More pertinent to our study are weird narratives that do reveal a supernatural entity. I term these “objective” because the impossible objects are represented as actually occurring in the mise-en-scene, rather than as figments of the protagonist’s imagination. As in Victorian ghost stories or the works of Blackwood, Wharton, or James (M.R. and Henry), many weird tales culminate in a glimpse of the impossible thing. The possibility that natural laws have been transgressed propels the narrative, which is brought to a climax by the revelation of the supernatural entity. These narratives present a real world that is intruded upon or interrupted in some way.

These movies are not the weirdest. In this part of our diagram, we find films that prolong the uncertainty before it culminates in unreal horror. Many of the most famous films categorized as horror prolong the sensations of weirdness as far as possible, before ultimately introducing the otherworldly. Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Don’t Look Now (1973), The Omen (1976), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), The Shining (1980), The Changeling (1980), and Get Out (2017) deploy this formula. These films, at the intersection of my diagram, might be considered weird horror; like Psycho, they juxtapose sequences in which the language of film generates curiosity, dread, and fear, moving from one dominant affective tone to the next. In terms of plot, they are immediately distinguishable from “normative” horror narratives, which introduce the monster much earlier (Frankenstein, Dracula, King Kong, Freddy Kruger, Cenobites, It, etc.), or graft horror onto a mystery narrative (e.g., Silence of the Lambs, Seven, etc.). Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) rightly stands as a masterpiece of weird horror owing to its ability to present an otherworldly monster early in the narrative while retaining the sense of subjective irrationality (paranoia, hysteria) and continuing to fuel our curiosity (because the monster has no fixed form). Recent films that reproduce this weird narrative include The Babadook (2014), It Follows (2014), The Autopsy of Jane Doe (2016), Annihilation (2018), Midsommar (2019), Color Out of Space (2019), Censor (2021), The Advent Calendar (2021) and In the Earth (2021). The films of Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead, discussed at length in a later post, follow this plotting, while incorporating surreal and metafictional signifiers of weirdness explained below.

Whether subjectively or objectively weird, the above movies depend upon normative narrative structures; scenes are mostly sequential in plots that follow one or two central characters as they brush against the boundaries of the rational and real. But since its inception, cinema has also explored the weirdness of discontinuous or dream narratives. Readers may be familiar with Un chien andalou (1929), Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), Kenneth Anger’s Magick Lantern cycle, The Hawks and the Sparrows (1966), Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) and The Phantom of Liberty (1974), Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977), Lost Highway (1997), and Mulholland Drive (2001), Being John Malkovich (1999), Holy Motors (2012) or The Green Fog (2017). While there are countless other “surreal” or “experimental” films that are profoundly weird, these suffice to indicate cinema’s equivalent to narratives that have long been a mainstay of weird fiction, from Lewis’s The Monk (1796), Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Kafka’s The Castle (1926) to the novels of Robbe-Grillet, stories by Shirley Jackson and George Saunders, or the Welcome to Night Vale podcast. These stories generate uncanny effects by dislocating normative storytelling procedures, adopting what Freud termed “dream logic.” They express the weirdness of cinema by allowing the cuts between frames to enter the narrative, as though the normally invisible movement from frame to frame and scene to scene were instead treated as a series of dislocations, delays, and new directions. Such films may or may not evoke the supernatural; frequently, as in The Phantom of Liberty, Eraserhead, or Holy Motors, they include supernatural elements among other, “real world” sequences. The primary sensations they evoke include a profound sense of the odd, disconcerting, and unaccountable. Because the effect is achieved formally, through parallel movements (Phantom of Liberty is disconcerting because there is no single protagonist; Holy Motors because the protagonist’s body moves between subjectivities; The Green Fog because representations of the subjects constantly change, etc.), the normative language of visual narrative becomes the impossible thing—ever deferred, like the meal in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. The weirdest director working in this tradition today is Quentin Dupieux, whose work will be discussed in detail in a later post.

The fourth modality for weirdness in contemporary film combines the previous elements by evolving the cinematic language of “found footage horror.” The use of “found footage” develops out of dada, surrealist, and other avant-garde methods of making films that surfaced in the 1960s, thanks to Super 8 cameras and the Pop aesthetic, which valorized reproduction and detournement; the first found footage films recycled/reappropriated rolls of film that had been shot for other purposes. The narrative conceit of “found footage”—shooting film that appears to be unedited footage but constructs a traditional narrative—slowly emerged throughout the 1970s and 1980s, before exploding in the 2000s, following the incredible commercial success of The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity (2007). Thousands of found footage films, nearly all marketed as “horror” movies, appeared in subsequent years. Few use footage that was originally made for other purposes; twenty-first century “found” footage exists as an aesthetic effect, not as the physical/political process of reappropriation.

The conceit these filmmakers deploy is two-fold. The first premise is that a nonfictional movie, usually a documentary, was the “original” goal of the production. Contemporary found footage films rely upon the concept of the “mockumentary”; actually, mockumentaries are foundational to this subgenre: Clarke’s The Connection (1961); Watkin’s The War Game (1966) and Punishment Park (1971); Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1980); Duncan’s 84C MoPic (1989); Belvaux, Bonzel and Poelvoorde’s Man Bites Dog (1992); and Avalos and Weiler’s The Last Broadcast (1998) use this formula to establish what will become a common narrative conceit. Importantly, the mockumentary enjoys equal if not greater success in comedy, with a history that includes Allen’s Take the Money and Run (1969) and Zelig (1983), Fellini’s The Clowns (1970), Idle and Weis’s The Ruttles (1978), Reiner’s This Is Spinal Tap (1984), Cundieff’s Fear of a Black Hat (1993), Guest’s Waiting for Guffman (1996) and Best in Show (2000), and Charles’ Borat (2006). In these films, weirdness takes the form of oddity, zaniness, and “cringe,” which is comedy’s version of torturous abjection. Occasionally (Penn’s Incident at Loch Ness (2004), Glosserman’s Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Version (2006); Clement and Waititi’s What We Do in the Shadows (2014)) mockumentaries strike a successful balance between comedy and horror.

These movies are non-normative in their use of a metafictional framework that generates a satirical/skeptical mode of enjoyment by asking us to reconsider both the “reality effect” generated by normal documentary filmmaking and the “reality” that we are pretending to observe, usually “behind the scenes” in one way or another. In the comedies, the weirdness of film finds figuration in odd-ball and wacky characters, be they automatons, clowns, queers, or maniacs. These misfits are negotiating the ‘ordinary’ (if equally ridiculous) ‘real world’ that is imagined to exist in the documentary background, and which becomes, through their strangeness, the object of a more subtle parody. Found footage “horror” (in this context it could be labelled “tragedy”) reverses this dynamic, putting a bunch of ‘normal’ documentarians in the foreground and figuring the otherworldly in the landscape. Our protagonists are ambassadors from the ordinary world who find what they were looking for: a background that consumes them.

The second, equally important conceit is that the production is severed by horror. Consequently, the footage is imagined to document not only the original production, but also the reproduction of the horror that interrupted it. The most frequently employed narrative involves amateur filmmakers who attempt to record the unknown turns into horror. This is the premise of Cannibal Holocaust, Man Bites Dog, The Blair Witch Project, Troll Hunter (2010), Grave Encounters (2011), The Conspiracy (2012), Digging Up the Marrow (2014), and dozens of others. We are asked to imagine that we are watching unedited footage in which a “real life” documentary becomes a survival scenario. (An important variation, the home movie, will be discussed in later posts.) Weirdness is generated at the level of plot and through the viewer’s engagement with the (imagined) documentary, which is viewed “against the grain,” i.e., with an eye for the discrepancies between subjective and objective realities.

Although frequently associated with low budgets, hand-held cameras, and improvisatory acting, the essential components of found footage films are not these stylistic features; on the contrary, the most important aspect is the metafictional frame. The premise that what we are watching is “real,” rather than the usual movie magic, is a conceit that returns us to the earliest examples of weird fiction, such as Daniel DeFoe’s A True Relation of the Apparition of one Mrs. Veal, often regarded as the first modern ghost story, and Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), a hoax which purports to be a “found” manuscript documenting impossible events. For centuries, the metafictional frame has been used to establish a strange relation between “documented,” eye-witness accounts and fictional scenarios. Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838) and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” (1845) use this technique, as does Verne’s The Sphinx of the Ice-Fields (1897), Manchen’s The Terror (1917) and Welles’ radio dramatization of The War of the Worlds (1938); an important variation (akin to the “home movies” in found footage films) is the diary, as deployed by Gilman in “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), Manchen in The White People (1904), Blackwood in “The Listener” (1907), and Klein in The Events at Poroth Farm (1972). The metafictional frames recast the reading experience in a manner that heightens weirdness—we are asked to scrutinize the ordinary with diligence, anxiously scanning for evidence for or against the narrator’s purported encounter with an impossible thing.

This metafictional frame is the conceit of all found-fiction films, but among contemporary found footage there is a subset of films which are particularly canny as regards the uncanny effects generating this enjoyment. In the aesthetic tradition of Cannibal Holocaust (which focuses upon the editing of the film itself), such movies as Skew (2011), The Conspiracy (2012), Creep (2014), Found Footage 3D (2016), Frazier Park Recut (2017) and Butterfly Kisses (2018) generate weirdness by introducing into the plot a perception that the supposedly “raw” footage we are watching (the original narrative conceit) has actually been “cooked” (edited) by someone (or something). The result is an intensely fertile environment for weird affects, and the best found-footage films recognize the full potential of this doubly-framed staging of reality interrupted by the Real.

Taken together, these aesthetic strategies suggest that a ghostly genre, weird cinema, has been partially obscured by the horrific, despite the differences between these affects and the modes of their aesthetic reproduction. The remainder of this essay is devoted to a close reading of affects in one of the most effectively uncanny films of recent decades, the 2016 British feature A Dark Song, written and directed by Liam Gavin and starring Steve Oram and Catherine Walker. I choose this narrative because its realism, subjective/ objective dynamics, prolonged hesitancy, and rejection of the horrible demonstrate the dominance of weird sensations in a film that is conventionally labeled as horror. As they say on Random Number Generator Horror Podcast No. 9, “Warning! Spoilers ahead!”

A Dark Song

As the film begins, Sophia (Walker) pays a handsome sum to lease a large estate in the remote Irish countryside. She is seeking privacy; her expressionless face holds back what the opening chords suggest will be a torrent of grief. The independent, distressed woman seeking refuge in an eerie house is a Gothic trope found in Radcliffe’s novels and Psycho; the melancholic protagonist, best dated to Hoffmann’s stories, occurs throughout the weird canon.

The cinematography emphases ordinary life as Sophia meets a dour man (Joseph Solomon, played by Oram) at the train station, and they travel to the rented house; she is consulting him for services that remain obscure. His abrupt questions transgress conventions of politeness, but she answers eagerly, establishing a master/disciple relationship, enforced by gender norms and economics (she is paying for his professional services), that develops throughout the narrative. The conversation reveals that, despite the visual signifiers of introduction, we have begun in media res. Their conversation is rife with signifiers that have more meaning for the characters than for us. She has begun a series of ritualistic cleansings. When he asks her why she seeks guidance, her answer, “for love,” sends him packing; as she drives him back to town, we learn that he’s been asked to perform what he calls the “Abramelin procedure”—a black magic rite for conjuring one’s guardian angel. He scornfully tells her that performing this rite “for love” is “like getting Titian to decorate a cake.”

The reviewer might pause here to explain this Kabbalistic arcana, based on a seventeenth-century grimoire and performed by Alistair Crowley, but the movie does not. The script will deploy numerous allusions to Kabbalistic and Gnostic texts and rituals, but Gavin’s choice is decisive: the film’s focus is upon the embodied and emotional significance of this profane act; its cultural baggage is discarded, just as the world will be left behind as the ritual commences. The movie would convince us that the ritual is real, but the power of its narrative derives nothing from the actual texts to which characters allude. This sets the movie apart, emphatically, from what I’m calling “weird horror” narratives, which inevitably introduce Gnosticism into the story. Here, our acceptance of the power of dark magic is beside the point; this is a narrative about Sophia’s acceptance of it. This focal point situates the film firmly within the ‘real’ world. Sophia is performing this ritual in an extension of our shared reality (rather than in a world that also contains supernatural elements). This is matched by an entirely conventional mode of cinematic storytelling. The cinematography is efficient, unobtrusive, without any of the surreal or metafictional elements that will be discussed elsewhere.

The magician agrees to assist Sophia only when she reveals another reason for her request: “My child died. I lost my child. He was taken from me, and it was my fault. I have to hear his voice again. I need to speak to him.” Her melancholic purpose convinces him that she is sincere and sets the tone for follows, while situating this narrative within a tradition of ghost stories and weird tales about the resurrection of the dead.

Back in the house, Joseph takes pains to explain the seriousness of their endeavor, while mocking Sophia’s cursory knowledge. “Real angels, real demons” should not be confused with “psychobabble bollocks.” There will be days of fasting, “back-breaking rites” and “ritual sex,” he cautions, underlining clauses in a contract; she remains undeterred. Joseph’s unstylish track suit, the shabby, post-war kitchen, unobtrusive camera work, and naturalistic performances underscore his insistence that Sophia ‘be realistic’ about their potential for summoning the impossible thing.

This scene, along with two that follow, clarify the dramatic forces that allow A Dark Song to intensify the weird “hesitation” longer than other films. Sophia’s determination, but also her psychological instability, is emphasized on her final trip to town. Shopping for their extended shut-in, she encounters her sister, who urges against this foolishness. Sophia demands that she not be interfered with; she is “doing something” to counteract the grief and no longer cares if it’s “godly” or not. In a juxtaposed scene, we glimpse Joseph at the mansion, printing pages off the internet—an activity he has berated Sophia for engaging in, and one that introduces the notion that he may be conman, taking advantage of her melancholia to extract not only the large sum she offers, but the food, shelter, and sex she will be required to provide. Sophia, the grieving woman, the disciple, must submit to Joseph’s dictates, which in the real world are of course “bollocks.” Since the film’s world is an extension of our own, and guardian angels do not exist, he can only be a grifter; on the other hand, we may consider him a professional in an unusual but not necessarily malevolent arm of the care industry, helping her through her grief by creating the ritual she believes that she needs—or, like Sophia, we may choose to accept his earnestness. He speaks and acts as though the magic were real.

If Joseph is scamming Sophia, his approach to gaslighting her is fiendishly clever; in the Crowley role, he insists upon his authority to determine the causes and consequences of every action, claiming, for example, that when she tells a half-truth, it causes him to nick his hand with a knife. By continually doubting her investment in the ritual (“this has to be pure,” he tells her) he causes her to commit more fully to a project, the parameters of which fall entirely under his determination. Her wish causes her to accept the possibility that invisible forces are at work.

This dynamic is symbolized by a ritualistic sequestration from the world. Joseph pours a line of salt around the outside of the mansion. Before completing it, he offers Sophia a final warning: “this is your last chance to back out. Once I complete the circle, no one can leave until the invocation’s done. Not for food. Not for emergency. Not for anything.” Completing this circle will lock them into the ritual—either through invisible magic or through mutual adherence to imaginary rules. “Seal it,” Sophia says. Her commitment is soon tested, for the next morning, when she seeks to assert a small degree of authority, reminding Joseph that she is paying client, he becomes violent, smashing a plate and hurling insults; for the ritual to work, she must accede all power. Under his supervision, they engage in a series of actions, each innocuous on its own. Geometric shapes are drawn on the floor, candles and objects placed about; there are phrases to be learned and foods to be consumed. Joseph provides vague, cliched explanations for what he requires. “For the next two days,” he tells her, “I’m going to unshackle the house from the world. You mustn’t leave the circle. No food, no water. Focus on the stone…”

These scenes occupy the first third of the movie. In the next third, we find ourselves sometimes identifying with Sophia, sometimes with Joseph, as each struggles to maintain their commitment to an arcane and obscure formula that must be followed to the letter. If these intensely realistic scenes may be read allegorically, the obvious analog is psychoanalysis. As analyst, Joseph insists that Sophia sit with her suffering; the only way through her grief is by touching the void (in the film this pursuit is perverse, since Sophia’s discourse is expressed through the closed symbolic structures of magic, rather than the open-endedness of words in the therapeutic setting, which go in search of their meanings). As the patient, Sophia perseveres; her search for signs that anything significant has occurred—that the ritual is working, as the weeks turn into months—organizes our experience as viewers, who also “anxiously scan” (a term discussed in later posts) for signs of the impossible. A Dark Song is “The Yellow Wallpaper” inside out. Our protagonist, confronting the loss instead of the arrival of her child, invites the male authority into the room, and they both attempt to peel back the paper, to discover the trapped thing underneath.

When the signs appear, the curiosity, hope, dread, and doubt that we experience through identification with the protagonists enters a phrase that is common to weird fiction, and which helps to distinguish these sensations from those more directly related to horror. Weirdness prolongs hesitancies and finds pleasure in the pain of not knowing; it values subtle shifts, slight changes in atmosphere or tone, hints and vagaries, uncanny slippages. By contrast, horror puts an end to not knowing; it insists that we confront finality, and so values the cut, the sudden, turn of events, and foreseen conclusions. A Dark Song prolongs weird expectation until the end. Sophia wants to believe in signifiers of the supernatural—the placement of a photograph, minor coincidences—that we may encounter as her delusions; Joseph insists that every event, no matter how insignificant, should be taken as a sign, yet we may doubt that he believes this. As we enter the film’s final third, it becomes unclear whether Sophia is experiencing hallucinations, brought about by the ritual, or we are witnessing the merging of worlds that Joseph promised. Like many of the movies mentioned above, as the film nears its climax, a variety of techniques are used to generate a surreal, hallucinatory sequence.

SPOILER ALERT! If you care about not knowing the ending, I hope you’ve watched the film by now because the final sequence is crucial to a claim regarding the aesthetics of weirdness.

In the final sequences, Joseph is dead and Sophia, who has confessed that she seeks not a moment of redemption with her son, but to damn his killers, is beset by phantom figures, which may be devilish spirits or figments of her devilish imagination. After confronting these demons, she wakes one morning with a new clarity. It is over. She has not found what she is seeking. In a daze, but aware of the gravity of her actions, she steps over the line of salt—and although the ritual has not been completed—nothing happens. The world does not end.

Sophia returns to the house. There is something there, in a room at the top of the stair. It is her guardian angel. It is beautiful beyond imagining. It brings what angels always bring: the miracle of forgiveness, acceptance, peace. Weird narratives need not end in horror. The uncertainty may result from or resolve itself into the miraculous just as well. And that is the truth of weirdness—its openness to the unknown is fueled as much by curiosity as by dread, for when the monster turns out not to be monstrous at all, the conclusion is only more satisfying.

Next in the Series

The next four posts in this series seek to elaborate the varieties of weirdness outlined above.

In the next two essays, I discus the work of two or three contemporary weird auteurs. The films of Quentin Dupieux are extraordinarily weird; Rubber (2010), Deerskin (2019), and Mandibles (2020), denature the monster of horror narratives, exploring how the impossible thing might enter the film’s reality in original ways. The films of Benson and Moorehead develop weirdness through a variety of diagetic and extradiegetic techniques, while engaging in the construction of a “mythos”—an intertextual world that is a peculiarity of the genre. In Resolution (2012), Spring (2014), and The Endless (2017), they bring together numerous elements of weird narrative, combining Lovecraftian horror with surrealism.

The two essays after that are devoted to exploring the found fiction phenomenon in detail. The first of these will touch upon “classics” of the genre, such as Cannibal Holocaust, Evidence, and The Blair Witch Project, in order to identify the significantly distinct narrative devices that make contemporary films, such as Evil Things (2009), Troll Hunter (2010), and The Conspiracy (2012) so effective. The second essay will examine found footage films that push the boundaries of weird narrative, such as Creep, Skew (2011), Grave Encounters 2 (2012), Digging Up the Marrow (2014), The Midnight Swim (2014), Butterfly Kisses (2018) and Char Man (2019). Such films present us with the “logical conclusions” to which this new subgenre’s techniques have led and suggest new directions for cinematic weirdness in this mode.