To begin with a confession: I’m no Lovecraftian. I admire a dozen of H.P. Lovecraft’s stories, particularly “The Statement of Randolph Carter,” “The Shunned House,” “The Dunwich Horror,” “At the Mountains of Madness,” and “The Shadow over Innsmouth.” I had the pleasure of teaching “At the Mountains of Madness” last year in a course on imaginary Antarctica, which also included Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Verne’s The Sphinx of the Ice Realm and LeGuin’s “Sur.” I’ve read most of Lovecraft’s stories, some of his essays, and a little of the academic scholarship. But I’m not a member of any Lovecraft societies, secret or otherwise, and my knowledge of his personal life is cursory at best.

This puts me in the target demographic for Paul La Farge’s The Night Ocean, published in 2017 by Penguin. I read the first half the first day I bought it; the pleasure was so intense that I felt myself falling out of life. The rest of my obligations would have to wait while I disappeared down this rabbit hole. (The second half was much less enjoyable, for reasons I’ll go into later.)

My interest in Lovecraft stems from his work in the peculiar genre of “weird fiction.” This genre peaked in the first decades of the 20th century; it mediated the relation between modern sciences (anthropology, geology, sociology, psychology) and the folk cultures these disciplines took as their object of professional inquiry. The genre’s most notable writers include Lord Dunsany, M. R. James, Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Ambrose Bierce, and Robert E. Howard also contributed important stories, as did Henry James in “The Turn of the Screw.” Edgar Allen Poe and Lewis Carroll were revered innovators. As a genre, “weird fiction” has two chief characteristics: an intense interest in intertextuality and metafiction, and a dedication to testing the limits of rational knowledge. Although weird fiction owes much to gothic romances, from The Castle of Otranto and The Mysteries of Udolpho to Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Poe’s “The Mystery of Marie Roget” best epitomizes the modernist approach. Poe’s fictional detective Dupin pokes holes in the real-life investigation into the death of Mary Rogers by deconstructing newspaper reports; his fiction turns the scientific investigation against itself, discovering clues in the lacunae of official inquiry. It blurs demarcations between fact and fiction while preserving the “mystery” of Rogers/Roget’s murder. Dupin ultimately fails to name the “true” culprit, but Poe succeeds in debunking the “truth” generated by modern investigative techniques. Lovecraft and the other writers of weird fiction follow Poe’s lead by undermining the modern “myth” of a fact-based, rationally coherent universe discernible through a combination of textual research and immediate experience. It was, in short, a kind of late romanticism: exposing the underside of modernism’s professional rationality. Its protagonists are almost inevitably gentleman naturalists or academic researchers who glimpse realms beyond the grasp of science.

Weird fiction’s exposure of the fictions involved in the construction of the modern world led writers to explore two variations on metafiction. The first depends upon the construction of fictional texts, which function as “windows” onto mysterious and illogical regions of experience. M. R. James’s ghost stories, each disclosed through an antique book, best exemplifies this preoccupation. In “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book,” the illustration in the back of a 16th century manuscript calls forth the demon it depicts; in “The Mezzotint,” the illustration of a house changes each time it’s viewed, depicting a child’s abduction; in “The Tractate Middoth,” a library book hides a will that conjures a ghostly clergyman. The texts inside texts (inside texts) heighten the realism of the unreal by distancing it from the reader’s life, while simultaneously magnifying the pleasures of reading.

The second variation reverses this logic. While weird metafiction continually reframes experiential reality, weird intertextuality uses multiple references to create a singular world. Otherwise unrelated stories reference the same mysterious events in order to convince the reader that something must actually be “out there.” Several of Arthur Machen’s stories are designed around this principle; for example, in “The White People,” various characters glimpse the titular monsters, an underground race whose existence has given rise to folklore about fairies, elves, and ghosts. The canny reader picks up on the overlap between narratives, thereby getting to “discover” a world that no single narrator quite understands. (If weird fiction’s intertextuality is neurotic, its metafiction is psychotic.)

One of Lovecraft’s great achievements was to combine both modes. He invented numerous fictional texts–most famously, the dread Necronomicon by “the Mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.” The book is referenced in many stories. He also invented Miskatonic University, in the fictional town of Arkham, Massachusetts. More than fifteen of its faculty–biologists, doctors, folklorists, geologists, psychologists, zoologists– glimpse a pantheon of aliens–Dagon, Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep, and of course the infamous Cthulhu. Likely, this was a clever tactic for pulp writers, whose work was less distinguished by authorship than by the worlds they created. Readers of Astounding Stories, Weird Tales, and other pulps returned to writers by returning to worlds.

The other and more important quality of weird fiction was the weirdness. Today, we might think of it as a literary confrontation with the Lacanian “Real.” Characters encounter a thing (usually a creature, but also art, architecture, feelings) that simply can’t be described. In his book-length essay, Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft pays no attention to the metafiction and intertextuality he mastered; his focus is entirely upon the literary production of fear. Folklore and organized religion, he argues, are “formalised” discourses designed to confront the biological fact that “we remember pain and the menace of death more vividly than pleasure.” Weird literature is sharply distinguished from horror, a discourse that is “externally similar, but psychologically widely different.” The latter involves “mere physical fear and the mundanely grotesque.” It doesn’t achieve a break from “reality.” (Think Stephen King.) Weird literature, by contrast, creates an “atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces” and a “particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.” Zizek couldn’t define the Lacanian Real better. An amazing book by Graham Harman, Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy, explores this confrontation with the phenomenology in depth (going back to Heidegger and Husserl) and breadth (discussing all of Lovecraft’s major stories). Unlike most commentators, who obsess over “the real” Lovecraft and/or his fictional worlds, Harmon focuses on the author’s “deliberate and skillful obstruction of all attempts to paraphrase him” (9). This stylistic feature explains Lovecraft’s contribution to (weird) literature. The trait for which some critics condemned him–his refusal to explicitly describe the “shambling horrors” his protagonists witness–is his genius. He advanced an insight nascent in Poe (the Freud to Lovecraft’s Lacan): that what is beyond reason is necessarily beyond the senses.

I love the first half of The Night Ocean because it plays with inter- and meta-textuality perfectly; I was disappointed by the second half because it refuses the weird. The former establishes La Farge’s novel as an enjoyable piece of postmodern, information-age fiction; the latter reveals a literary pretension inimical to weird fiction, which (as Lovecraft suggests in Supernatural Horror) was always a popular, rather than highbrow, genre.

The novel’s narrated by a New York psychoanalyst named Marina Willett. Her (possibly deceased) husband, Charles, was (or is) a freelance reporter specializing in profiles of the “almost famous.” His stories bring to life the hopes and travails of those who dedicated their lives to ideas that never took off. His final and most successful project attempts to expose Lovecraft’s sexuality: was he asexual (as most official biographies portray him) or a repressed yet practicing homosexual? Charles discovers Lovecraft’s Erotonomicon, a diary detailing sexual encounters with various young men, but especially Robert Barlow, a teenage fan with whom real-life Lovecraft visited for several weeks on two occasions. Lovecraft’s letters and biographies tell us that the notoriously reclusive writer spent a surprisingly large amount of time at Barlow’s parent’s house in Florida and made the teenager executive of his estate. They collaborated on a half-dozen stories, including “The Night Ocean,” from which La Farge’s novel takes its title. In La Farge’s novel, we learn that the story, which describes a young artist’s glimpse of a merman–”a swimming thing emerged beyond the breakers. The figure may have been that of a dog, a human being, or something more strange.”–can be interpreted as an expression of Barlow’s or Lovecraft’s “obscene” desire. I give little away when explaining that the Erotonomicon turns out to be a hoax inside a hoax. Since Poe’s “The Balloon Hoax,” the ability of texts to deceive us has been a staple of the genre.

La Farge spins an enormous and intricate web of intertextuality and metafiction as Marina recounts how her husband discovers Lovecraft’s journal of sexual exploits. In numerous excerpts from the diary, Lovecraft refers to himself as “the Old Gent” and to sexual acts as magic rituals and monstrous creatures readers of his stories know well. Upon arriving in Jacksonville, Florida, Lovecraft meets a boy at his hotel:

No sooner had I got my hat off and my stationery unpacked then he was scratching at the door, insinuating the he knew certain rituals which would turn even the oldest flesh to stone. For $1.25–how they are cheap down here! No morals, I suppose, to pay the price of–I had an Ablo and two Nether Gulfs. That showed him what old flesh can do! At least when warmed by the Florida sun . . . The imp limped out round-eyed, and offered to return in the morning with another of his brotherhood. (36)

A footnote (one of the novel’s delights are numerous footnotes, some meant to be from editors of the Erotonomicon, some from Marina) supposes that “Nether Gulfs” refers to “Active anal sex,” but notes that “Lovecraft refers to that act elsewhere as ‘the Outer Spheres,’ but, confusingly, he also uses this second term to mean orgasm” (36). Pointing out the uncertainty of the text’s weird signifiers is a technique Lovecraft used in many stories. In La Farge’s novel, it queers Lovecraft’s fantastic terms, a kind of laughing jab at readers who would prefer to think of these fantasies as exercises of “pure” (i.e., asexual) imagination. At the same time, as the above passage suggests, the Erotnomicon exposes Lovecraft as recognizably queer. The boy knows the Old Gent’s desires at a glance, playing on the idea of a subcultural system of signification that straight readers have missed.

References to the real world grow more intense as Marina traces her husband’s research into Robert Barlow. The real-life Barlow transcribed many of Lovecraft’s manuscripts before studying anthropology at several universities. Specializing in Nahuatl, he took a position at the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. His prodigious scholarship earned him a Rockefeller Foundation grant and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He chaired the Department of Anthropology at Mexico City College, before committing suicide in 1951, apparently because his homosexuality was about to be exposed. Among his students was William S. Burroughs, who wrote to Ginsberg of the “queer” professor’s death. Burroughs is one of many real-world characters that show up as we learn of Barlow’s life among early science-fiction fans in New York and radical artists in Mexico. With intense detail, La Farge imagines scenes drawn from Barlow’s biography. As a member of the “Futurians,” a proto-Marxist avant-garde sci-fi club, Barlow joins Donald Wollheim, Frederik Pohl, Robert “Doc” Lowndes and other writers and publishers for the first World Science Fiction Convention, held in New York in July, 1939. The story of their attempt to wrest science fiction away from “the fascists” is written with joyful intensity. They design costumes and print manifestos in a beat New York apartment:

Pohl took the cutout fabric to the window and sewed up the legs of Lowndes’s suit by hand, but we had all overlooked the fact that Lowndes was three-dimensional. He hopped around with one leg in the space suit, one out. “What are you people doing?” asked Wollheim, who had just come in. He had been in Pohl’s bedroom, typing up a leaflet with the Futurians’ demands, to be handed out at the convention. “We need a steamroller to flatten Lowndes,” Pohl said. “We need s-s-someone who knows how to s-sew,” said Michel. “Forget the costumes,” Wollheim said [. . .] He handed a mimeograph stencil to Michel. “I figure we need two hundred copies.” Over by the window, Pohl dropped a cigarette into the paint can. “Is paint flammable?” he asked no one in particular. (256)

I don’t know to what extent these details are “true to life.” I hope they are mostly invented. La Farge’s ability to (re)create the fan’s sensibilities–overlooking Lowndes three-dimensionality, proposing to flatten him to fit the costume–puts him on par with the very best postmodern novelists, such as Don Delillo, Katherine Dunn, Thomas Pynchon, and David Foster Wallace. Pynchon’s epic tale of turn-of-the-century cultural anarchism, Against the Day (2006) frequently came to mind. Like that book, The Night Ocean moves effortlessly across space and time, without forsaking minute details of mundane life.

Matt Keeley, reviewing the book for Tor.com, is exactly right when he argues that “While it hasn’t been marketed as such, La Farge may have written the first great novel of fandom.” Along with the above authors, we get gleeful glimpses of Isaac Asimov, Ursula Le Guin, Robert Bloch and other science-fiction luminaries.

The playfulness borrowed from the early life of science fiction fades away in the novel’s rather tedious final act. Simply thumbing through the book reveals this difference. The first several hundred pages are full of journal entries, footnotes, transcripts of interviews and twitter feeds. The second half settles into much more conventional prose, with almost no intertextuality. Similarly, the story shifts away from real-world characters to focus upon a fictional character named Leo Spinks, whose life-story takes us to small-town Canada, the recently liberated Belsen concentration camp, and suburban New York. Without giving too much away, the second half “undoes” the first half. It replaces the queer Lovecraft with accounts of Spinks’ straight marriages, and replaces the fandom with sober portraits of holocaust survivors and bitter housewives.

To me, this swerve away from the weird feels like a retreat from the pleasures of weirdness. It exposes the century-old distinction between modern literature and genre fiction. Had the novel gone the other way–bringing us further into Lovecraft’s “atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces”–it would have committed itself to the low-brow plots of pulp stories. Instead, La Farge contains his horrors within the bounds of historical reality. He chooses to write a paraphrasable novel in the end. Writing for the Washington Independent Review of Books, David Z. Morris, regards the straightening out of weird fiction as a positive. The Night Ocean, he writes, is “happily free of any version of Lovecraft’s own iconic creations. This separates it from a rather pathetic subgenre of work that waves a lot of tentacles around and calls it ‘homage,’ [. . .] the core achievement is darkly sublime, a translation of the cosmic insanity of Lovecraft’s work back into the human realm.” J. W. McCormak agrees; in a review for Culture Trip, he observes that La Farge’s novel “returns Lovecraft and his ambiguous legacy to the world as we know it, which is, oh yes, much more horrible than any ‘Colour of Space’ or squamous Cthulhu.”

It’s interesting to consider why these readers approve real-world horrors over fictional confrontations with the fantastic. Why is Lovecraft’s ambiguity such an offense? In the first half, La Farge suggests that we fear weirdness because it brings us into contact with repressed sexuality. Lovecraft’s barely discernible monsters allow us to catch glimpses of what Freud (in a phrase Lovecraft would love) called “polymorphous perversity.” Our infantile fears and desires are inseparable and infinitely malleable; “growing up” requires the separation, repression, and straightening out of these feelings, to produce a subject that fits into social norms. In this sense, The Night Ocean “matures” from a work of fan fiction into an adult novel.

One of the book’s best details is young Bobby Barlow’s bedroom closet, where he keeps his collection of pulp magazines. The closet is named Yoh-Vombis, after a story by Lovecraft’s colleague Clark Ashton Smith called “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis.” In the Erotonomicon, Lovecraft first propositions Barlow while they sit in the closet, thumbing through a fanzine:

I could help myself no longer, and asked whether there might be a secret panel in the back of this closet which led to another closet, where he kept the truly accursed volumes of his collection. He professed not to understand what I meant: was I looking for something by Charles Fort? Yet I thought that in the back of his eyes–which are pale brown, by the way, and much magnified by his glasses–I saw some tremor of interest. (37)

The best parts of The Night Ocean discover closets within closets within closets, and resonate with a jouissance that balances innuendo with the fan’s delight in minutiae. Less interesting is the labor necessary to put all of this back into the closet before the novel’s close.

Last week, I observed a comrade’s son reading

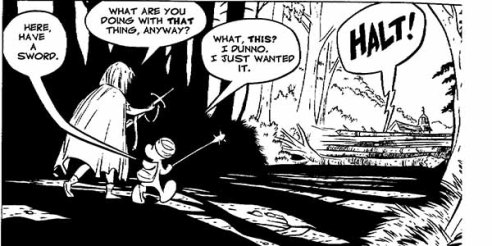

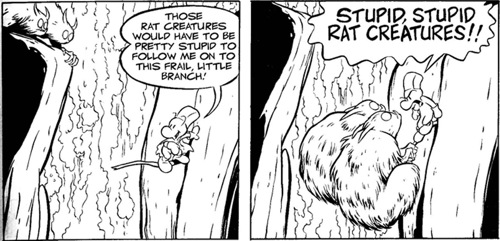

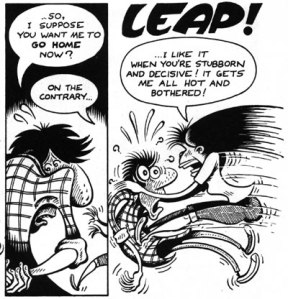

Last week, I observed a comrade’s son reading  The original comics were black-and-white, pen-and-ink drawings. Before they were colored, Smith’s drawings depended upon the size and shape of lines, along with the spacing of narrative elements, to develop complex characters, slapstick humor, and fast-paced action. He contributed to the innovations in the use of negative space and “slow motion” that Frank Miller popularized in Ronin and the Dark Knight. But more like Hergé than Miller, Smith focused on a precise rendering of panel-by-panel actions and reactions. His work resembles Saul Steinberg’s in it’s love of the pen and George Booth’s in the the care it extends to the minutia of details. But Smith does more; he uses two graphic styles to represent a fundamental rift in his world. Bone and his cousins are Pogo-like cartoon creatures, drawn with thick, smooth lines. The residents of the valley in which they find themselves are human and animal, rendered with thinner, scratchier lines. The Bones’ bodies are empty of all but the most significant details; the human and animals bodies are more fully “filled in” with textural marks. In other words, two styles share many frames. Compare this to Miller’s two realities but single style in Ronin or the distinct styles of Jaime Hernandez’s Hoppers vs Gilbert’ s Palomar. In Bone, characters from one stylistic reality (cartoonish / clear-line) find themselves in a world dictated by a different stylistic reality (realistic / textured).

The original comics were black-and-white, pen-and-ink drawings. Before they were colored, Smith’s drawings depended upon the size and shape of lines, along with the spacing of narrative elements, to develop complex characters, slapstick humor, and fast-paced action. He contributed to the innovations in the use of negative space and “slow motion” that Frank Miller popularized in Ronin and the Dark Knight. But more like Hergé than Miller, Smith focused on a precise rendering of panel-by-panel actions and reactions. His work resembles Saul Steinberg’s in it’s love of the pen and George Booth’s in the the care it extends to the minutia of details. But Smith does more; he uses two graphic styles to represent a fundamental rift in his world. Bone and his cousins are Pogo-like cartoon creatures, drawn with thick, smooth lines. The residents of the valley in which they find themselves are human and animal, rendered with thinner, scratchier lines. The Bones’ bodies are empty of all but the most significant details; the human and animals bodies are more fully “filled in” with textural marks. In other words, two styles share many frames. Compare this to Miller’s two realities but single style in Ronin or the distinct styles of Jaime Hernandez’s Hoppers vs Gilbert’ s Palomar. In Bone, characters from one stylistic reality (cartoonish / clear-line) find themselves in a world dictated by a different stylistic reality (realistic / textured).

It’s more complicated than that, of course, because Phoney also wants to get them safely home; he’s just convinced that a large amount of loot will help them on their way. Like Scrooge McDuck, he suffers from an intense money fetish. When Smiley and an orphan rat creature they’ve named Bartleby figure out how to coin money, Phoney weeps with joy. By contrast, Bone’s Caspar the Friendly Ghost, a frequently ignored superego that hovers near by, lamenting bad decisions when he’s not saving the day.

It’s more complicated than that, of course, because Phoney also wants to get them safely home; he’s just convinced that a large amount of loot will help them on their way. Like Scrooge McDuck, he suffers from an intense money fetish. When Smiley and an orphan rat creature they’ve named Bartleby figure out how to coin money, Phoney weeps with joy. By contrast, Bone’s Caspar the Friendly Ghost, a frequently ignored superego that hovers near by, lamenting bad decisions when he’s not saving the day.